Thank you Rod Carr for the excellent seminars listed below. We appreciate all the help, wisdom, on the water tactics, equipment, and time you have given.

VICTORIA SEMINAR SERIES – 1

GENERAL APPROACH

- Each seminar will discuss a topic from each of the three areas shown in the diagram. We will focus on basic topics first to provide a foundation for later, more detailed discussion.

- Topics will be chosen that can provide immediate improvement to race course performance.

INTRODUCION

Sailboat racing as an activity is incredibly complex. Since R/C racing puts the entire responsibility for performance on one person, that is an even more intense load of information that must be processed and timely decisions made. The skipper of an R/C yacht simultaneously fulfills the roles of:

Captain Helmsman Tactician

Sail Trimmer Rule Interpreter Weather Observer

The trick is to figure out which role should have priority at any point during a race. Setting that priority is often a result of experience, but some focused study can assist in developing that experience.

Before one goes out on the race course, there are a few questions that one should ask him/her self:

1) What is your overall goal for 2010? Be realistic, what do you think you can accomplish with reasonable effort during the 2010 season?

- What are your specific sub-goals relating to:

- Boat configuration and function?

- Understanding the rules?

- Being able to mentally model the course and its wind field?

- Observing changes in wind and wave during a race or series of races?

Having set your goal, you need to commit to a formal methodology for measuring your progress toward those goals. I recommend a little, hardbound notebook that fits in your toolbox. This will be available at the end of each sailing event for you to record your evaluation of the day’s events while they are fresh in your mind.

In your regatta log you should enter:

- What two things did you do well?

- What two things did you do poorly?

- How do you assess the tuning and sailing performance of the boat (as distinct from racing performance, i.e. finish position, etc.?) How did the boat perform compared to other boats….to weather, on the reaches, down wind?

- What adjustments, modifications, or maintenance should you accomplish before you sail again?

Writing these things down before you leave the lake takes self-control. But over the course of a season you will be surprised how the fixing of a whole bunch of little things as soon as you discover them can add up to major cumulative increases in boat reliability and performance.

ENVIRONMENT – SURFACE WIND STRUCTURE, TRUE/APPARENT WIND

- The wind presents a velocity profile with wind speed increasing from essentially zero at the surface, to free stream velocity above 10’ to 15’. For purposes of Victoria sailing, we may consider the wind speed at the masthead to be roughly twice that at the bottom of the mainsail.

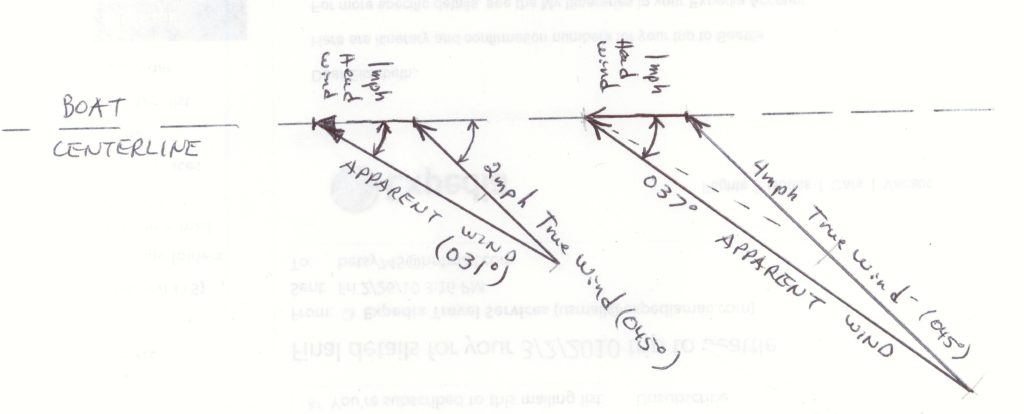

- A boat sailing to weather sails in what is called the apparent wind. This wind is the vector addition of the true wind and the head wind generated by the speed of the boat through the water.

- On the beach, a boat set up on a stand has no component of apparent wind due to speed through the water as it does while sailing. So the sail will respond to the wind’s changing velocity profile, but there is no corresponding change in direction as one ascends since the boat feels only the true wind under this scenario. One cannot really assess the appropriateness of the twist set in the mainsail, by holding the boat up to the wind. It must be assessed on the water

DEFINITIONS

Back – when the direction the wind comes from swings to the left.

Veer – when the direction the wind comes from swings to the right.

BOAT – MAINSAIL SET UP, TWIST, CONTRIBUTION TO WEATHER HELM

- Goal is to match the entry angle of the sail with the apparent wind direction at any height.

- Since the apparent wind draws aft with height, the sail must twist off to leeward as one goes aloft.

- The first approximation for setting this twist is to put the bottom batten parallel to the centerline of the boat, and allow the clew to lift until the top batten is parallel to the boom. This sets the twist in the sail. Adjust the main sheet to set the angle of attack for the sail that gives you the pointing performance needed for the existing wind and wave conditions.

RACING – WIND LADDER, STARTING LINE

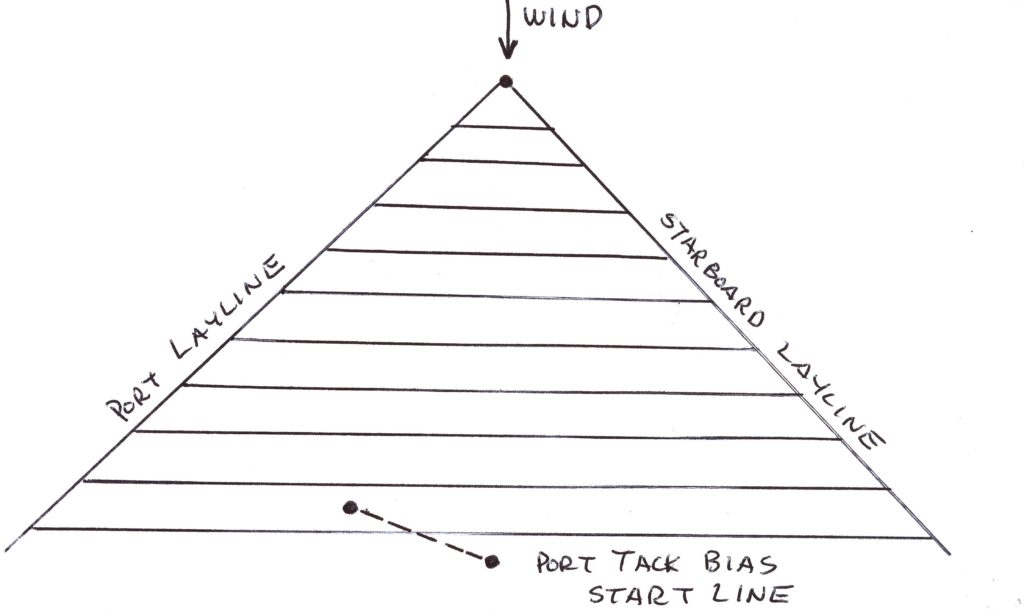

The concept of a wind ladder, horizontal rungs between the port and starboard tack laylines to the weather mark, where boats along any given rung have the same distance to travel to the mark. Pivoting the laylines and horizontal rungs at the weather mark gives a graphic example of what happens to boats as the wind veers and/or backs.

Plotting a starting line between the laylines shows which end is favored, and allows determination of new starting line strategy if the wind direction changes after the starting line has been laid.

VICTORIA SEMINAR SERIES – 2

ENVIRONMENT II – THE WIND FIELD

Reason for Study

The intent is to use the April 2010 Green Lake Regatta starting line and weather leg as a means of illustrating the kind of analysis that needs to be undergone to maximize one’s performance at the start and on the weather leg. This analysis will be different in detail, but not in methodology when the wind blows from other than the northwest, and the starting line is located somewhere other than the southern boundary of the course. Those with an interest, can make a major contribution to their understanding of the Green Lake site, i.e. develop the depth of their knowledge of local conditions, by carrying out the analysis for every 30° of true wind direction from south to north.

The weather system wind chosen for reference in the analysis is the wind that is blowing at the outboard end of the starting line.

General principles that seem to apply at this sailing site are:

- The more perpendicular to the shore, i.e. nearer to 270° the wind blows from the more the wind will lift off the water as it approaches shore, producing slower moving air near the water.

- The more obliquely the wind blows toward the shore, the more of a channeling effect will be produced and the more the wind will be bent by the influence of the shore.

- Definition -The Wind Field: A map of the local wind direction blowing over the race course at any one time.

Features to note: Changes in wind direction caused by proximity with the shore; changes in wind velocity across the race course. Affect of a change in direction of the weather system wind, ….a veer, ….or a back.

RACING II – APRIL START AT GREENLAKE: A CASE STUDY

Based on our discussion of the wind field, we are now ready to use that understanding to plan our approach to the starting line, and the subsequent strategy to be employed on the weather leg.

- Is the starting line square? I.e., can you cross the line at a 45° angle on starboard tack?

- If not, how is the starting line biased? Which end of the line is closer to the weather mark?

- Why start at port end? Why start at starboard end? What are the risks involved in either choice?

- Where do you want to be 1 minute after the start? Why? Where should you start to accomplish that strategy?

BOAT II – ASSESSING WINDWARD PERFORMANCE

- The Polar Plot

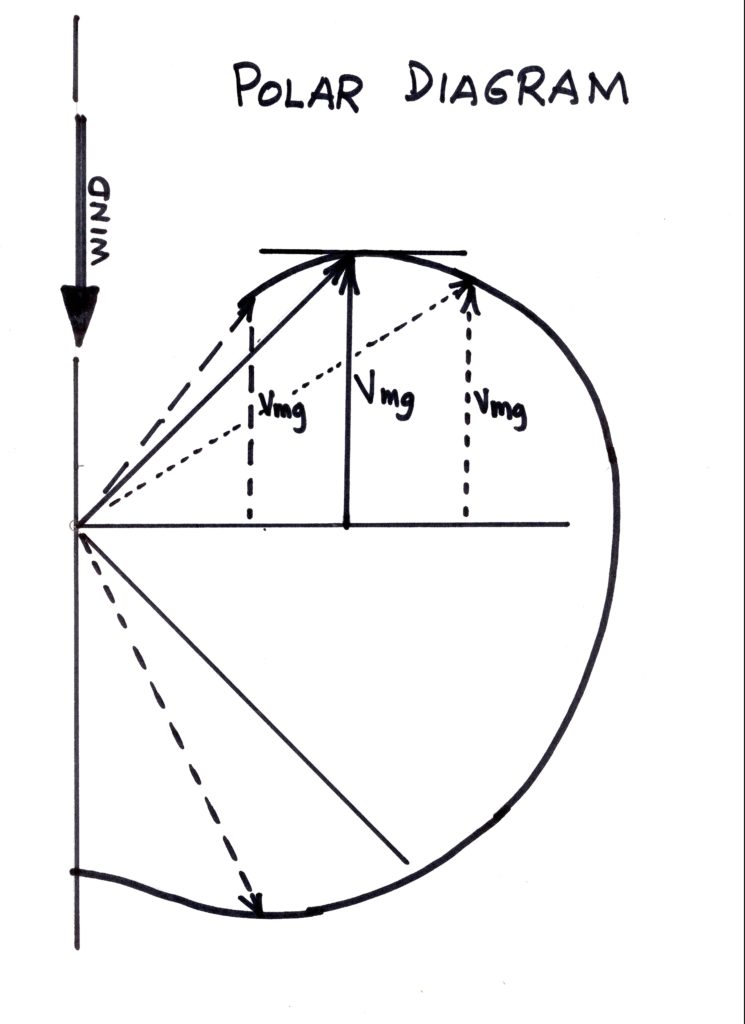

The polar plot shows the speed of the boat through the water on any point of sail relative to the true wind.

- Vmg – This is the bottom line of windward performance, it is the vector that measures the boat’s progress dead to windward, into the eye of the true wind. It is one component of the vector representing the movement of the boat as a result of its interaction with the relative wind in which it sail. Vmg is hard to measure without reference to other boats. Hence, the following discussion that uses the yardstick of a nearby boat as a means of evaluating the state of tune and trim that results in good windward performance.

- Wind Vane/Masthead Fly – Wind Vane shows direction of relative wind. Mast head fly or a long masthead telltale gives some general directional information as well as an indication of relative wind speed.

- Telltales – On the mainsail leech are used to monitor airflow over the upper half of the mainsail, the power plant of the boat.

- Definition – Scalloping: Increasing the distance made good to windward, by alternately pointing closer to the wind until speed starts to decrease, and then footing off to gain speed, following by pointing up again. This can be accomplished by using a “dog-leg” winch arm that allows the jib sheet to be slacked before measurable movement of the mainsail sheet occurs. Slacking the jib sheet, will allow the mainsail to scallop the boat to weather without rudder movement, while pulling in or hardening the jib sheet will hold the boat’s bow or head off the wind allowing speed to build back up.

- Setting the Jib

- Jib Twist – sweep of the jib leech should match that of the mainsail when viewed from astern. Assess again when the boat is launched, adjust as necessary.

- Setting the slot – In general, “when in doubt, let it out”. But, also use the middle stripe on the mainsail to assess when the jib is far enough in to just begin to occasionally backwind the mainsail.

- Assess the entry angle displayed by the mainsail. If it is too large, it can cause backwinding. This can be eliminated by adjusting the mainsail luff tension and mast shape.

ASSESSING WINDWARD PERFORMANCE

While sailing during the month of May, compare the performance of your boat with a near by boat as you both sail to weather in the same wind. Compared to the other boat does your boat:

Point Higher or Lower?

Move through the water faster or slower?

Heel more or less?

Does what your boat is doing impede your ability to get to the weather mark before the other boat?

The next Seminar will deal with these issues in some detail. So take time during May to do some observing, and maybe even write down some of the observations that reappear every time you sail.

VICTORIA SEMINAR SERIES – 3

ENVIRONMENT III – READING THE WIND ON BEATS

First – measure the wind speed. There are many inexpensive anemometers available. One of the best is the Dwyer Wind Meter. Cheap, easy to carry, and needs no batteries.

Watch the rise and fall of the Dwyer, and you not only get instantaneous wind speed, but you can see the extremes of gusts and lulls, and after a minute or so will have a pretty good idea of the average wind speed you are going to be dealing with.

Second – determine the wind direction. A wind vane mounted on top of your mast is an excellent source of information. Make it well balanced, light weight, and very visible. Alternatively you can watch the vanes on other boats, but this removes your eyes from your boat and may be less than efficient.

Changes in wind direction produce significant changes in the position of the “wind ladder” that we discussed in the April Seminar. So learning where the average wind is coming from and when it changes can produce meaningful gains on the racecourse. This is especially true where the sailing site has a pattern of repetitive or oscillating shifts where the wind switches back and forth between two average positions.

Green Lake oscillating shifts are typically S – SSW – SW in 4 – 10 minute patterns.

Coulon Park shows them as SE – SSE – S in a 5 – 15 minute pattern.

Bellevue Pond shows them SE – SW in a rapid 30 sec – 3 minute pattern.

How does the boat respond to changes in the wind’s direction and velocity? The quick answer is a change in heel angle, and a change in boat speed. Together these can combine to produce a change in course as the hull form immersed in the water changes. Increasing heel, will generally produce additional weather helm as the bow is driven into the water and the boat rotates around the keel fin with the bow coming up into the wind.

Is it possible to conclude what the wind is doing by watching the boat? In general terms it is, but with experience you will soon be able to do a better job of reading the signals. Since the true wind can 1) Change speed; or, 2) Change direction lets list what the boat does in each case.

A1) If the true wind speed decreases, the boat’s heel angle decreases, the boat’s speed decreases and the apparent wind moves forward, to keep the sails full, bear off carefully.

A2) If the true wind speed increases, the boat’s heel angle increases, the boat’s speed increases, and the apparent wind draws aft, so allow the boat to point up higher to follow the change in the apparent wind angle.

B1) If the true wind direction draws forward, your wind vane will point more forward, the boat’s heel angle decreases, the boat’s speed decreases and the apparent wind draws forward, so to keep the sails full, bear off carefully.

B2) If the true wind direction draws aft, the wind vane will draw aft, the boat’s heel angle will increase, the boat’s speed will increase as the apparent wind draws aft and you may allow the boat to point up higher to follow that wind.

For know, be cognizant of these changes and observe the boat carefully as the wind changes its speed and direction. Since both direction and speed changes can happen simultaneously, they can reinforce or oppose one another. This gets complicated quickly, and we’ll deal with it later after we have more observational experience.

BOAT III – PRACTICE SAILING FOR IMPROVING PERFORMANCE

GOAL

To develop confidence in the boat and its configuration so that one can focus on strategy and tactics of racing, and observing the wind and wave conditions.

Without doing some structured practice sailing with a partner, one will not develop an understanding of boat tuning for best performance. Sailing the boat efficiently needs to become second nature so that one can observe the wind and wave conditions and their minute to minute changes; think about the strategy and tactics available to take advantage of these changes; and respond to the other boats on the course in compliance with the racing rules. If approached seriously, practice sailing will allow you to set your boat up for the conditions and then make only minor changes after the first race. From then on, you can focus on the racing, rather than the boat.

Without writing down the key characteristics of your set up, you will have to rely on your memory, and since the list is 6 to 10 points long, you risk forgetting something. At the end of a practice tuning session, you should have the following in your log book:

- Wind Speed

- Close hauled – a) End of main boom distance to centerline; b) Jib club distance

- Mainsail foot camber

- Mainsail twist

- Jib foot camber

- Backstay tension

- Mast shape

- Topping lift adjustment

- Battery position

- Mast location (if moveable), jib swivel location (if moveable)

Practice sailing is done in pairs. Two boats sailing to weather 3 – 4 boat lengths of separation sailing toward a windward mark. Sail steadily, when ready, weather boat calls “Tacking in 3 – 2 – 1!” Return down wind, then pause. What did you observe?

Pointing – How did boats compare?

Boat Speed – How did boats compare?

Tacking – How did skippers compare? Which boat retained way better?

Helming – Was course essentially straight, or did it wiggle a lot?

Repeat this 8 – 10 times. Now, one or the other boats is faster. Take the boats out and compare their sail set and close hauled trim. What are the differences between the boats?

Pick one difference and adjust the slower boat to match the quicker one. Only change one thing at a time, or you will not develop any specific information. Enter the water and repeat the sail exercise.

Repeat the exercise. Once the boat’s are basically equal in performance, the skipper’s should swap boats and repeat the exercise.

When finished, pull the boats out and record the information in the list above. A table can eventually be constructed with wind speed across the top, and the other measurements down the left hand side. With reference marks on the deck, booms, etc., you’ll soon be able to come to the lake, measure the wind speed and immediately set your boat up for the existing conditions.

RACING III – LEEWARD MARK ROUNDING

- Not overlapped upon entering the 4-boat circle

- Same tack

- Opposite tack

- Overlapped upon entering the 4-boat circle

- Same tack

- Opposite tacks

VICTORIA SEMINAR SERIES – 4

BOAT IV – STANDING RIGGING

Purpose of Standing Rigging:

- To establish and maintain mast configuration consistent with desired sail shape,

- To develop jib stay tension so that jib luff is properly formed,

- To prevent any change to 1 or 2 as a result of typical wind speed variations.

Victoria’s have what is termed a “fractional rig”. This means that the jib stay intersects the mast a distance below the masthead. That intersection point is then locked in space since it is the vertex of a triangle made up of the mast below it, the jib stay to the deck, and the deck between those two. If you wish to change the location of the intersection point, you must either a) shorten or lengthen the jib stay using the same intersection point; or b) change the intersection point using the same length jib stay.

Jib stay sag is inversely proportional to jib stay tension. I.e.; more tension, less sag. Increasing backstay tension increases tension in the jib stay. It can also cause movement of the mast head aft, thereby releasing the upper leach of the mainsail. Such aftward movement can be countered by increasing tension in the jenny or diamond stays if they are rigged. If they are not rigged, the only way to get power back into the mainsail is to release the extra tension in the backstay. In addition, increased backstay tension will tend to bow the center of the mast forward, unless restrained by lower shrouds attached at the level of the spreaders. Without lower shrouds forward movement of the mast will flatten the mid-body of the mainsail, decreasing power. Excessive movement forward will produce an “overbend” wrinkle, a diagonal crease in the sail running from the spreaders aft and down to the mainsail clew.

Sideways bend of the top of the mast will cause the unsupported upper mast to bend off to leeward levering the middle mast to weather, opening the slot. Side stays and spreaders resist this and keep the mast in column. Upper mast bend off will also release the upper leach of the mainsail, depowering the sail during a puff, just when there is extra power to be had and a chance to scallop up to weather to gain distance to the weather mark.

All in all, skimping on standing rigging will not gain performance. Minimalist riggers spout theories about reducing weight aloft and saving windage. My counter is that rigging wire doesn’t weigh anything, and I have yet to have won a race by being able to coast into the wind better than the competition.

ENVIRONMENT IV – THE WIND’S INFLUENCE ON THE START

Before starting the first race, it pays to consider the wind direction and any observable shifts so as to form the basis for a starting strategy. You should carefully note:

- Wind direction relative to the starting line. Which tack is favored at the line?

- Wind direction relative to the weather mark. Which tack gets to the mark most efficiently?

Crossing the line repeatedly before the racing starts will help you visualize the wind regime that exists for today’s sailing. It is not foolish to sail for a half hour before the first start to determine what kind of shifts are occurring, how fast and of what magnitude.

Wildly biased starting lines are not seen as much any more as the fleet has gained experience in mark setting, and in a willingness to reset the starting line if conditions change.

RACING IV – PLANNING YOUR START

First, assess what kind of a starting line has been set:

- A square line is perpendicular to the true wind, and boats on both tacks will cross such a line at an angle of 45°.

- A biased line is not perpendicular and will favor one tack over the other. Some lines are so biased that a port tack start is worth the risk.

Second, decide how you are going to define a “good start”. Some examples are:

- I cross the line at the gun in the first tier.

- I cross the starboard end of the line after the gun to weather of the fleet.

- 30 sec after the gun I can tack as I please to clear my air.

- 30 sec after the gun I have clear air and can tack when I want to.

- 30 sec after the gun I am on the favored tack to weather of the fleet.

- 30 sec after the gun I have split from the fleet looking for salvation.

Now, what kind of an approach will give you this result? Remember that the past behavior of the fleet can be a key component of a starting strategy. How does the fleet you sail in handle the start? What characteristics can be used to your advantage? Which ones can cause your trouble?

Have you noticed:

- The port end of the line is often littered with boats that were too early?

- The starboard end of the line has a handful of boats barging, coming in wide above the close-hauled lay line to the starboard mark. A leeward, starboard tack boat on that lay line need not let them in. Practice a close-hauled approach to the mark crossing at the gun, and you can turn away all those bargers.

- Occasional boats starting on port either by approaching the port pin, or by reaching down the line on starboard, then tacking at the gun.

VICTORIA SEMINAR SERIES – 5

BOAT V – Running Rigging

Mainsheet – Close Hauled

Three Sail Stick Trim Positions – Trimmed In: Point higher, but may slow

Centered: Setting for best Vmg.

Trimmed out: Point lower, footing for speed

Unlike rudder trim which must be switched from side to side on the transmitter as the boat assumes a new tack; sail trim acts the same on each tack and does not need to be adjusted when tacking, unless there are new considerations requiring a change on the new tack.

Jibsheet – Close Hauled

Three Sail Stick Trim Positions – Trimmed In: Sail lower, jib holds bow off wind

Centered: Setting for best Vmg.

Trimmed out: Point higher, mainsail pushes stern off the wind

With only one channel for sail control, a means has to be found to separate the affect of the sail trim function between the jib and the main. The reason is that when trimming in, for example, the main tries to make the boat point, and the jib tries to oppose that by holding the head off the wind with a tighter jib setting. We would really like to done one of the other by adjusting the trim lever. This can be done in the boat by using a bent SCU arm. You have to decide which sail you want to move with the trim lever, and at the closehauled position have that part of the arm off the centerline of the boat, while the other part of the arm is right on the centerline. Either sail can be chosen and there are reasons to choose, and reasons not to. An analysis of your own sailing style should guide you.

RACING V – Starboard Tack Roundings

When required to pass marks to starboard, complications occur in the vicinity of the mark. Boats on starboard tack retain their rights whether inside or outside the 4 boat-length circle, as long as they stay on starboard tack. But since they have to tack at some time to round the mark, when they pass head to wind and are tacking they no longer have right of way, and until they are on the new tack with sails filled, they must keep clear of other boats, and on the new tack cannot force those boats to sail higher than close hauled.

One way to simplify the situation is if approaching the mark on starboard tack, approach the mark far enough downwind that one can tack outside the 4 boat length circle and slightly beyond the layline so as to not get caught in a raft up of those who are still tacking in the circle.

ENVIRONMENT V – Observing the Wind Direction

Watching the heel angle of a boat sailing can give some clues as to both the wind speed and wind direction. The information is bundled together, and requires some thought and experience to separate, something we don’t really have time to do on the race course. Of the two, direction has the most immediate relevance because one needs to sail on the tack that approaches the next mark the quickest. That there are different wind speeds across the course is something that needs to be considered more in planning how to sail the course and its several legs. But instantaneous understanding of what direction the wind is coming from near the boat directly impacts tactical decisions on how to get to the next mark most efficiently.

The value of a mast top wind vane cannot be over estimated. It gives one the ability to tell whether the wind direction is changing, or that it is dropping when the vane moves toward the centerline of the boat, giving an indication of the “boat speed wind” the wind generated by the movement of the boat through the water.

At Coulon Park, several of the IOM fleet members have been carrying very long streamers at the masthead. A few instances of very light wind were encountered, and without enough way to make the rudders effective, these boats were seen to drift off down wind, probably because of the drag of the streamers at the mast head. The waving streamers do give a somewhat general picture of wind direction, and by their whipping about also an indication of wind speed, but the former is not very precise, and the latter can be gained by the skipper pointing his nose into the wind and listening to both his ears.

Without a wind vane, one is left to observe other boats and use information from those observations to guide choice of tack and other tactical considerations. Having a vane, puts immediately useful data right on the boat where it can help in tactics, and in helming the boat more efficiently.